Розин Марк

УПРАВЛЯЮЩИЙ ПАРТНЕРWhat Is the Culture of Achievement, And Why Is It Important For Business?

Prologue

I would like to start with a case I personally observed and, moreover, in which I participated. A young and ambitious graduate of a Western school of business became the CEO of a large industrial holding company. He was not happy with the bureaucratic, procedure-oriented management system he found, to a large degree "manually operated", despite all the bureaucracy. One of the first innovations he launched was a bonus rewards system for managers based on KPI (Key Performance Indicators). The KPI system was indeed introduced a few years later. However, a closer look would reveal that KPI definitions came out looking somewhat odd (e.g., "performing without deviation from plan"), in most cases "challenge" equaled "target", inevitably 100% fulfilled by the managers. Bonuses were paid accordingly, at a 100% rate, and whatever additional funds became available, they were still manually distributed as before. The holding company was still as procedure-oriented, bureaucratic and manually operated as ever. Why? Isn't it true that the CEO introduced an appropriate and systemic approach (not by any means manual) to developing KPI and adequate goal descriptions? It is obvious that the holding company's corporate culture "devoured" the new management system. As a rule, introducing new people or designing "correct" management systems proves a vain hope in terms of changing an organization, because managers fail to acknowledge (or cannot control) the existing corporate culture, which in most cases is stronger than both, whether it be an individual (even an excellent leader), or a deliberately designed approach.

Corporate culture is one of the most decisive factors for success, yet something extremely ephemeral and elusive. Even though it takes place directly in front of our eyes, it is quite difficult to change and even more difficult to measure. No product or tool is as much desired and demanded by businesses as a model describing corporate culture evolution that would allow for the exercise of control over it.

Spiral Dynamics

In 1990s two management consultants, Don Beck and Chris Cowan, proposed an approach to how organizational cultures can be described and controlled, based on the original work of the psychologist Clare Graves. Their model postulates that individuals, groups of people, social institutions, companies and even whole countries in their development go through typical stages best represented as a spiral. People and communities as they develop and pass from one stage to another, ascend on a spiral, hence the name of the approach, i.e. Spiral Dynamics.

Followed by Cowan and Beck, Graves was aspiring to build a universal model equally applicable to individual development and to change in human societies. This model is thoroughly described in Spiral Dynamics by Beck and Cowan, a book also available in Russian[1]. Proceeding from that approach, we have spent close to fourteen years to refine the model adjusting it to business needs and obtaining a working tool that allows for performance of the following tasks:

- diagnose the dominating culture of an organization (or a mix of cultures if several are present);

- identify conflicts caused by cultural friction between different parts of the organization and propose methods for their resolution;

- predict the effect of interactions between different parts of an organization based on their "cultural profile";

- evaluate potential difficulties when introducing organizational change (such as reorganizations, mergers, etc.);

- make a prognosis about the viability of a certain management system;

- predict whether a given person will thrive in a company;

- select leaders capable of taking the company to a new level of efficiency.

The article was written to highlight all these issues.

We will start by describing typical corporate cultures forming a spiral. As we move forward, we will note particular features of the model that emerge in the process of spiral-like upward movement. Then we will draw some preliminary conclusions as to the model as a whole, and pass on to discuss the practical tasks it allows to address.

But before we begin we need to agree on the term "corporate culture". What exactly is it?

What Is Corporate Culture?

I do not want to pile up cumbersome definitions, thus unleashing a heated debate on the "right" definition for the purpose. I am hoping to get out of the predicament by paraphrasing Norbert Wiener, the father of cybernetics: "I cannot give you a strict definition of corporate culture, but I know it when I see it". On an intuitive level, we often get a feel for the local corporate culture as soon as we enter the building. But to adequately describe it, we need to make sense out of the values and priorities shared by the majority of employees. These are the values and the priorities responsible for how an employee reasons, what choices he or she makes in a given situation, what decisions are made, and how they are explained. For this reason, I will portray certain corporate cultures by listing their key values and add an informal definition which will sound like the culture's typical answer to "Why are we acting like this?".

Other important characteristics of corporate culture include leadership style and existing management systems. However, it needs to be clearly understood that those are nothing but an extended consequence and a result of key values for this culture.

The Culture of Belonging: "Because This Is The Way We Do It"

Most companies start as a small team in a close, informal relationship often resembling a family (and sometimes growing out of it). This is the reason why culture of belonging, with its family values, can normally be seen as a starting point from which corporate culture later evolves. What is of primary importance to its members is to feel part of the team. A member is to a large extent prepared to sacrifice own interests for the sake of the group. Work in these cases is closely intertwined with private life, and many people go to work as to their "second family". The major images for this culture are family, tribe or clan.

A clearly delineated distribution of responsibilities is absent, with everyone doing what is important for the "family" at any given moment in time.

In a similar culture, the leadership role is usually performed by the person historically at the helm. He is not necessarily endowed with brilliant leadership qualities, or may have a paternal attitude of "just taking care of the family". The source for his authority, at any rate, has little to do with his personal powers, but is rather linked to the history of the company, its lore and tradition, including its commonly shared "myths". Their staple answer to "why are we acting like this?" is usually "because this is the way it is done", or "because we have always done it like this".

This is a very teamwork-oriented culture with such key values as belonging (therefore the name) and commitment to the team. It is to a large degree based on the human need to be part of a community.

As its business develops, the company is no longer comfortable within the close confines of a "family". Ambitions grow, family warmth goes away, individual team members copy their leader's behavior with the resulting struggle for power, initially hidden, but then becoming evident. Competition and a feeling of enmity build up, the unified "tribe" splits up, and the culture of belonging comes to a crisis.

Crisis

A crisis of growth is not anything unique to the culture of belonging. The path from one corporate culture to another always passes through a crisis.

Each culture is effective at a certain stage of the company's life cycle. I would like to especially emphasize this statement: there is no such thing as an absolutely "right" or absolutely "wrong" culture, each is good in its time and place, each is damaging under a different set of circumstances. What is noteworthy is that the same characteristics that are making a culture effective, also impede its further progress. This may happen because of company growth, or due to the personal growth of most employees, getting tired of the existing culture with its specific traits.

The major reason for the crisis of the culture of belonging is its lack of individuality (people have a problem promoting themselves within this culture) plus a management system locked onto the pater familias, which simply does not work with a grown-up company. That is why this culture is replaced by a cult of strong personalities vying for power - a culture of power.

The Culture of Power: "Because I Said So"

A culture of power is characterized by plenty (and sometimes by an excess) of leadership. Leaders who made it to the forefront in the times of the crisis, engage in severe competition, often ignoring rules and conventions. Each is after constructing their own autonomy, separating themselves from the others and creating a personal zone of influence which no one would interfere with. The company develops a cult of strength, the environment becomes more aggressive. "The right of the strong" and "all is fair (not so much in love as) in war" become the leading principles. The epoch of feudal fragmentation in medieval Europe can serve as a good example of this.

Even though it may not look very appealing, a similar culture is a step forward, as it represents a transition from mono-leadership to multi-leadership. Such aggression fills the company with energy sweeping away all that was earlier thought of as an insurmountable obstacle.

A muscle-flexing, authoritarian hard-liner - in biological terms, alpha male - becomes the company's leader. He hogs all possible authority and forces others to follow his lead through many decisions of blatantly arbitrary nature. Here the answer to the reasons for this or that decision more often than not sounds like "because I said so". Others obey the leader and copy his behavior at their level. The leading (if not the only) management system constitutes a direct order to be strictly obeyed.

As a company develops, this culture, too, starts to decline. The source of its crisis lies in the never-ending war between "principalities" - a fight without rules, which starts eating away at the company's energy, making it weaker before outside competitors. An increasingly unconstructive atmosphere and combat fatigue gives people (and, primarily, leaders themselves) a desire toreach an agreement and start playing by the same rules. The culture of power is replaced by the culture of rules.

A Pendulum and an Onion

As we observe the transition from the culture of belonging to the culture of power and the crisis of the latter, we get a hunch that will later be confirmed: corporate culture fluctuates back and forth between community spirit, conservatism, willingness to sacrifice own interests, monolithic stability, on one side, - and individualism, expansion, self-expression, changeability, and individuality, on the other. This pendulum sets forth the spiral motion, where every full swing brings the company back to the basic values it earlier rejected, so it would rethink these values and move to a new level.

The pendulum concept is reflected in the color-coding of the cultures. Each culture is represented by a certain color which in one way or another is associated with its leading values (for more details see the above-mentioned book by Beck and Cowan). Cold gamut is used to denote community-centered, collectivist cultures, warm gamut – individualistic cultures.

The second pattern is not so easy to detect, as it becomes manifest only after a careful analysis of the evolution of corporate cultures. With the transition to a new culture, a company does not fully reject the preceding culture, but intrinsically preserves its typical modes of thinking and decision-making as a base for the next “cultural layer”. Teamwork, typical of the culture of belonging, becomes a pillar for leadership in the culture of power. Individual power, in its turn, becomes an important tool for implementing and maintaining the system of rules, and so on. This means that a developed corporate culture resembles an onion containing all former tools in its depth, and they can be produced at any moment and made available for use if the environment so requires. As a culture becomes more complex, the array of systems available to it, is growing wider, making the company more flexible and adaptive.

Culture of Rules: «Because Those Are the Rules”

Looking for analogies in the history of societies, we can possibly compare the emergence of the culture of rules with a single national government taking place of many warring principalities. This process cannot be accomplished without a large number of formal and fixed agreements. A bureaucracy, at least its good aspects, can serve as an image for the culture of rules.

Someone living in a culture of rules (also called a culture of order) is convinced that the world is revolving around the rules, and they cannot be broken even for the sake of the most splendid achievement. The company’s atmosphere once again loses individuality. Stability, reliability and discipline become its key values. Business processes in the company are strictly regulated (in fact, this culture engenders the preoccupation with business processes), mandatory procedures and regulations become a key management tool. Typical justification for any decision sounds like this: “Because those are the rules”.

Culture of rules comes to a crisis because it is not sufficiently result-oriented. It is more and more often felt that, while the company is busy with paperwork and bureaucracy, its more aggressive, pro-active, flexible and dynamic competitors are skimming the cream off the market. The realization comes that, in the apt words of Grace Hopper[1], “It’s easier to ask forgiveness than it is to get permission”. A culture of success is growing on top of the culture of rules.

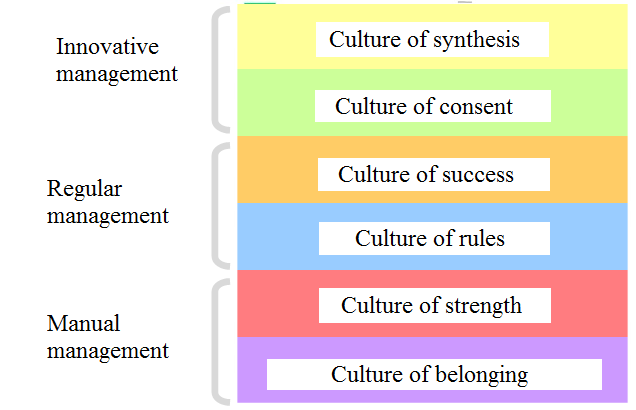

Leadership Borderlines and Regular Management

As a company moves into the culture of rules, we observe two new phenomena that are important.

First: the leader no longer wields unlimited power. The leader, like others, is now obeying the rules. This marks the transition from absolute leadership to management.

The second is closely linked to the first: the coming of the age of regular management. The two preceding cultures (culture of belonging and culture of power) handled management manually. Now, however, a company can be managed without direct leader involvement, using procedures and regulations.

The Culture of Success: "Because This Gets Results"

In full compliance with the onion metaphor, the culture of success does not abolish all rules, but places them in the background and supplements them with the core value of the result. People operating in this culture know that winning counts more than playing by the rules. For this reason, they are directing their efforts to the best possible result, break records, exceed expectations, try to do better than colleagues and recognized champions. The culture of success is very competitive, with competition of a different nature compared to the culture of power: a war in one case, Olympic games in the other.

The management system, accordingly, is aimed at achievement: ambitious goals become its core component. The culture of success explains decisions by stating, "This helps us reach our goal", or "This brings result".

Scalability

The culture of success is the first culture scalable with relative ease. Contrary to all preceding cultures, inevitably winding up in a crisis as companies grow, this does not happen to the culture of success. Success is structured is such a way that it does not break connections between different successful parts of the company regardless of size.

Nevertheless, the culture of success has its own vulnerabilities: constant pursuit of fast results always delays action on “maintenance” issues to an indefinite “later”, with long-term problems going unattended, thus today’s success may undermine that of tomorrow.

One more reason for the crisis has to do with the human factor, i.e. an emotional burnout that may occur in the course of this race for success. Excessive focus on record achievements eventually leads to frustration at any possible outcome: having accomplished the goal, a person feels emptied out; not having accomplished the goal, with the opportunity gone forever, makes a person bitter. In addition, this culture typically lacks warmth in interpersonal relationships, and its individualistic nature impedes teamwork. Sooner or later people get tired of constant Olympics, they want to take a break and look around without anyone breathing down their necks. What is budding now is the culture of consent.

Optimal Culture For Business

At present the culture of success is the most effective choice for a vast majority of business organizations. It combines respect for the rules which allows management to perform in a systemic way, without constant manual adjustment. It ensures adequate interaction without unconstructive conflict. It is oriented precisely to business success, since its core values correspond to business values: to get a bigger share of the market, to win, to maximize capitalization, to follow the most ambitious strategy without breaking the law, or to optimize costs, - in other words, win the first prize. Finally, on a personal level, the leading motive of this culture is the idea of prosperity and well-being, which is also in sync with today's understanding of business. Simultaneously, as I said before, this is the first culture on the spiral which is not jeopardized by business growth. Efforts to preserve all preceding cultures, despite business growth, are inevitably fraught with stalling in place and by the accumulation of unresolved issues, whereas the culture of success demands constant expansion.

My reader may get the impression that I am contradicting myself, since I stated earlier there are no good and bad cultures, but each one is valuable in its time and place. This, however, is not a contradiction: today's environment makes the values of success an optimal choice for the best business practices. In other places, depending on circumstances, a different culture might be more viable, e.g. a small, book-club type library might thrive with a culture of belonging. When the business environment changes, business thinking will change too, and it is possible that a different culture will become optimal for doing business.

Culture of Consent: "Because We So Agreed"

The key values for the culture of consent are dialogue and search. In this culture everyone knows that people are different, but they are not just putting up with it, they are willing to derive the most valuable resources from the fact. The importance of having multiple approaches to resolving the same task is well understood, regardless of whether they all will come in handy at the moment or some can be reserved for the future. The goal is not to win the Olympics, rather is to lay the foundations for the company's long-term development. And the quick success of the moment, which produces fast results, can be sacrificed for the sake of the future.

The culture of consent is about brainstorming, discussion, creativeness and participatory decision-making. It sets up reliable communication channels between different levels, divisions and functions in a company. A council of the wise who have great respect for one another is the central image of this culture. Decisions are based on consensus: "Because that's what we agreed on". Facilitation, understood as carefully leading people to constructively discuss a problem, is the main management tool in this culture.

J.R.R.Tolkien's Fellowship of the Ring is a wonderful illustration of this culture: a number of very different beings go on a quest together, benefiting from each other's strengths and capabilities, tolerant of each other's weaknesses, negotiating and using their differences for the good of all.

In today's environment this culture will not fit every business. However, it is extremely productive for the parts of the organization responsible for making important, long-term and strategic decisions, i.e. where quality counts more than speed: e.g., it is well suited for executive boards and boards of directors.

Innovational Management

Transition to a culture of consent brings about a new type of management: regulatory management is replaced by innovative models of management. This is an experimental ground where we can observe matrix organizational structures, an abundance of projects, an absence of hierarchy or fixed assignment of roles, teams are flexibly formed to fulfill a specific task and may not have a leader at all. This is the realm of controlled chaos, with an emphasis on awareness and the expertise of people who are prepared to ally with each other and negotiate for the common interests.

Culture Mimicry

As we look up and down the spiral, we notice that some cultures look alike. Thus, the culture of consent in its outward appearance sometimes resembles the culture of belonging, while the culture of success resembles the culture of power. At first glance, they may easily be confused.

This implies two important consequences.

First, it is important to look at the values rather than behavior. The same behavior may be prompted by vastly different values.

Second, overly energetic endeavors to spur the evolution of a corporate culture may result in a simulacrum of a higher culture mimicked by a culture of a lower level on the spiral. Sometimes this produces a very comic effect:

Prime Minister. Your Majesty! You know me for an honest old man, frank and direct. I always speak the truth, even if it hurts. I've been here the whole time, I heard you... let me use the right word... wake up from your sleep, I heard you... let's call a spade a spade... I heard you laugh. And... Your Majesty, let me be very direct...

The King. Go ahead. You know I never get cross when you speak your mind.

Prime Minister. I will be bold and direct the way old people are: you are a great man, my Sire![1]

But in many cases it is not nearly funny: cultural mimicry to a "higher" level translates as further deepening of the crisis and a decrease of the company's efficiency. (By the way, can you tell which culture is mimicking which in the above quotation?)

For example, the culture of power sometimes mimics the culture of success. The reason is obvious: the culture of success is attractive, and it is tempting for a business to try to jump to it ahead of time. A company declares that competition inside it will follow strict rules and performance will be assessed by KPI, but the truth is that the rules are constantly broken, and KPI - bent to existing accomplishments. On the outside, the system may even appear as working, but those inside it know very well that the company continues to function as a culture of power.

The Endpoints of the Spiral: Culture of Survival and Culture of Synthesis

In the lowest part of the spiral there is a culture we skipped in our discussion - the culture of survival. It is an absolutely individualistic culture where everyone is careful to avoid danger and satisfy their immediate needs, and where all alliances are of a purely situational nature, turning to dust as soon as they are not needed any more. This culture can be observed among people at the mines or trying to survive in a besieged town. It is incompatible with the very idea of organization, that is why, as I said before, evolution of business companies starts one step higher. In some extreme cases corporate culture may degrade to a survivalist culture - in this case, organizational values lose all meaning, people are solely preoccupied with their own interests, and in practice no one identifies with the company. In fact, this means organizational death.

The highest end of the spiral represents the culture of synthesis. This culture, too, can hardly be observed on a corporate level, as it is almost exclusively seen as a system of values cultivated by individual persons. The main reason for it is its paradoxical affinity with the culture of survival. Beck and Cowan subdivide cultures into groups (they refer to them as levels). The ground floor is occupied by the cultures from survival to consent, whereas the culture of synthesis starts the second floor, which in its structure resembles the first, but at a higher level of development. Where the culture of survival reflects values of struggling loners, the culture of synthesis represents values of creative loners fighting for self-realization. Members of synthesis culture want to develop themselves and create space for the development of other people, look for a break-through, for the solutions of the furthest future, improve their country and the world as a whole. These people make extraordinary leaders who know how to act at any level of the cultural spiral (Beck and Cowan refer to them as spiral masters), but they do not gather in organizations.

Beck and Cowan place one more culture above the culture of synthesis (Graves indicates even two), but I never had an opportunity to observe them in practice, therefore a detailed discussion would be a purely academic exercise, very removed from real life.

Geography and Industry Distribution

Evolution of corporate culture, according to Beck and Cowan, is a way the system of values and thinking in people or organizations responds to changing living conditions. Geographic location, historic time, current problems and circumstances are the key elements of living conditions. Describing the business environment in Russia, we must note that geography here behaves as "frozen time" (moving further away from big cities is like traveling back in time), and all issues and circumstances are extremely industry-specific. This means that particularly striking manifestations of a given culture are to be found in specific locations and specific industries.

I cannot endeavor here to put together a complete and coherent picture of similar trends, but will give you a few vivid snapshots.

Cultures of rules, of power, and belonging are typical for Russia in general, with the exception of Moscow and St. Petersburg. The culture of power is by far dominating among them. Moscow and St. Petersburg can be viewed as melting pots where everything can be found, and no culture can be singled out as predominant. By way of comparison, American companies most often cultivate a culture of success (which they also try to export to their international branches), whereas culture of consent is more often seen in European companies.

Geographical trends are combined with specific industry features. For instance, small regional branches of many banks can be described as a culture of belonging, pretty much representing the Soviet heritage. The same can be said about most pharmaceutical chains. Manufacturing industries in Russia mostly belong to the culture of power with an addition of values from the culture of rules (those companies are more effective) or from the culture of belonging (and those would be less effective). The academic domain is more pervaded by the culture of power (the fight for autonomy, grants, etc.), regardless of how much we would expect it to thrive as a culture of consent.

With severe competition inside an industry, there is a pressure in the direction of a "higher" culture, so that the culture of success is quicker to spread in the most competitive industries.

Here we will finish our quick examination of the dynamic spiral of corporate cultures and pass on to practical tasks this model allows to address.

Multiculturalism: How Different Cultures Interact Within an Organization

A monolith corporate culture is rarely found in large organizations. As a rule, the culture is different in different parts of the company. On the one hand, this may make an organization even more effective compared to a monocultural one (one culture provides the resource of togetherness, the other gives energy). On the other hand, a disparity of values may lead to serious conflicts if the combination of cultures is mismatched. What would be a "good match" then?

To get a better understanding of this, let us start with the question of how different cultures interact at various hierarchical "floors" of the company. The general pattern looks like this: parts of the company in the adjoining "floors" will be in perfect harmony if the culture above is one step higher than the culture below it.

For example, an adherent of the culture of power supervising people with the values of belonging is a viable design. Authoritative and paternalist leadership style will be accepted by the employees as entirely natural, while their family spirit will be acceptable to the leader. Conversely, if, all of a sudden, the pater familias starts engaging in regular management (i.e., a culture of rules), the "belongers" will feel uncomfortable, missing the feelings of caring and support on the part of their leader, emotional guidance and nurturing, "prodding" in the right direction, and even little punishments. They will feel alienated by the new atmosphere. Besides, the both cultures - rules and belonging - are of collectivist nature, which will lead to insufficient leadership energy, and the company will be "bogged up".

If we take the culture of success, it can perfectly well subordinate people from the culture of rules: the employees are disciplined and prepared to act, while the energy, the drive and goal-setting come from above. Conversely, employees from a culture of power will compete with the leader and, unlike him, without any orientation to result as a higher goal - a situation which may lead to a business collapse.

The list of examples can be continued (culture of consent in the board of directors, combined with the culture of success in upper management, etc.), but the basic principle will remain the same.

Any design, with a lower culture above and a higher underneath, is very unconstructive and conducive to conflict. To take one example, a typical situation in Russian manufacturing companies can be described as top management professing the values of the culture of power, and operating divisions living by the culture of rules. Willful and arbitrary decisions from higher up constantly annoy and confuse people responsible for the production, who have an acute need for systemic and rational guidance. As a result, the company is always smoldering in a conflict.

At first sight, the issue of cultures interacting "horizontally" appears more convoluted. However, any horizontal interaction is triggered by the chain leader who in fact "commissions" all others to perform given functions. In a growing market this role may be played by the operating/manufacturing division, in a stagnating market - by the sales department. Upon identification of this key player, it becomes easy to formulate the terms for horizontal harmony: the "commissioner" must be one step above other players.

Following the Thread: How Corporate Culture Can Be Changed

Can the corporate culture be purposefully changed? Yes, it can. However, I would like to warn you against one common mistake. In the situation where prevalent values are those of belonging and of power, it is always tempting to speed up the process, skip a step and jump directly to the culture of success which appears the most effective. I must admit that I also fell for this dream more than once and spent a tremendous amount of effort to keep myself and the client in check. Unfortunately, all that will be accomplished in the best case scenario is an early set-on of a crisis leading to the next step, and the process will be particularly innervating and energy-consuming. In the worst case scenario you will remain in the same place, or possibly even roll back one step.

In order to understand how it works, let us look at the culture of belonging and what happens to it when evolution is prematurely forced on it. If we decide to immediately replace it with a culture of success, then the absence of respect for rules and procedures will result in a culture of power. An attempt to introduce a culture of rules will be fruitless, since both cultures (rules and belonging) are of collectivist nature, therefore lack powerful leadership energy, without which regulations will not work, and not even a culture of power will come into being. It means that ways to perform a transition to a culture of power need to be found. All attempts to skip evolutionary steps bring the result comparable to that of trying to drive in a screw with a hammer.

So how can we change cultures, introducing the one we want? Here is the basic principle: new cultures are implemented with the help of the instruments of current culture, sometimes using the preceding culture as a stepping stone. To implement a culture of success, we must use the culture of rules, launching a very ambitious KPI system with goals on the brink of barely possible, even if at some places it needs to be pushed forward by force. To implement a culture of rules, we need to rely on the authority and leadership qualities of a specific circle, the members of which would get together, agree about the rules and make them into a law, using their energy and calling upon common interests, etc.

It would be difficult to provide more specific recommendations, since a wide array of methods is available, and it is impossible to make the right choice without taking into account a variety of factors and important considerations in any given situation.

Corporate Culture and Man

What happens when people adhering to certain values find themselves in a culture with different values?

In the case of a rank-and-file employee, there are only two possible outcomes: either adopt the leading values of the company or eventually drop out. In the case of a decision-maker, there are two additional alternatives which are more interesting.

The first one, with the person sufficiently charismatic and engaging, the "alien" may become a reformer, and eventually revamp the company's culture to something more fitting for this leader. As we have seen, the situation of a boss, who is one step more advanced than the others, should not be a problem, and this design can be productive without radical change. If the leader is more than a little advanced, he or she would have to be strong and patient. It is particularly desirable for the leader to be able to make good sense of the situation (for instance, applying spiral dynamics) and take one step at a time, trying not to jump ahead of developments, so as not to force and rip the "thread". Conversely, if the leader is less advanced, the situation will result in a conflict, but "cultural degradation" in a company will occur only in extreme cases.

Secondly, in the absence of charisma, the company's medium may "isolate" the leader with differing values, the way a body envelopes a thorn or a splinter isolating it with a sort of a capsule. In this case no amount of rules introduced by a culture-of-rules proponent will help them spread outside one single office, and no amount of orders issued by a force-oriented leader will help them be heard and obeyed, and so on.

On the whole, the same patterns are true for situations of mergers, whether they involve divisions or separate companies. The predominant culture will either win, or (much less frequently) cultures will constructively interact, or there will be a smoldering conflict, and those who cannot adjust, will leave the company or recede inside a cocoon.

Corporate Culture and Management Systems

As we described cultures, we mentioned that each of them uses management systems that are typical for it, with the room for management systems only appearing at the culture-of-rules level, because up until then the company is managed manually, in a hands-on fashion.

Let us take a look at how the system of financial motivation evolves from culture to culture.

The use of performance criteria and performance-based bonus awards is typical for the culture of rules. These could be process KPI or something simpler, but what is important here is the measurement-centric approach and predictable stable agreements.

The culture of success shifts the focus to the result. Compare two KPI definitions: "sell 870 million rubles worth of product" and "meet the annual sales target". The two appear identical (provided the sales target is numerically the same), but the focus is different. The focus is now changed to ambitious goal-setting as part of KPI, with primary attention given to the "challenge" benchmark positioned at the high-end of theoretically accomplishable. And the KPI structure itself is aimed at promoting each employee's personal responsibility for fulfilling every one of them.

The culture of agreement generates a large number of team KPI because of the assumption that there is a need to motivate teams rather than individual people. The idea of a balanced system of indicators is also part of this culture as something allowing to shift the focus from quantitative results here-and-now to qualitative achievements in a more long-term perspective.

What will happen if we attempt to introduce a mismatched management system? The answer will be along the same lines as when we analyze interaction between culture and individual: either the system will help the organization transition to a different culture, or mimic it and become completely diluted.

A transition to a different culture happens when all fundamental prerequisites already exist, and the system itself satisfies the requirements of the next-level culture. For instance, introducing bonus award criteria in a culture of power is a sign of nascent stable agreements which brings the company to the culture of rules. However, criteria may dwindle to a formality, with rules existing on paper, indicators kept track of throughout the year, but when pay-time comes rules are ignored and the boss rewards whoever, in his opinion, is more deserving. Similarly, ambitious goal-setting under KPI has the power to advance an organization from the culture of rules to the culture of success, but may also deteriorate to a formal procedural system devoid of ambition and non-consequential to motivation.

This is exactly what happened in the situation described in the prologue. The system the new CEO tried to implement (i.e., KPI-based bonus awards) matches the culture of success. A person with success values, he made an attempt to use methods typical of success culture, he articulated a set of KPI for his direct subordinates and delegated the rest of the process to them. Since the company lived by the power values with some elements of the rule culture, the KPI system came out as a formal process totally unrelated to result and of no use to anyone.

What should have been done instead? The CEO had two basic options:

- Try to implement a culture of success using methods of rule culture (describe step-by-step implementation procedures and design the system itself to the minutest detail), possibly applying pressure and using strength here and there to overcome the resistance.

- A less ambitious option would be to implement a system matching the nascent culture of rules, i.e. introduce quality performance indicators (which was in fact done by the company itself, except without much meaning, since it lacked outside guidance). True, these would not have built a bridge to much desired success - but would still ensure the company's upward advance on the spiral.

Let me say in conclusion that this discussion remains valid not only for system-building management tools, but for any change in a company. Understanding the laws of spiral dynamics significantly facilitates any process of introducing change. As an example, let me refer to our own experience of resolving a small predicament.

A few years ago ECOPSY moved to a separate, stand-alone office, which meant that we now needed to address all security issues ourselves. Before that, showing IDs to security personnel at the entrance had been somebody else's requirement and therefore accepted as unavoidable, but in the new situation this arrangement needed to be initiated by the company's management. The difficulty consisted of the fact that ECOPSY prides itself on its corporate culture of success, whereas showing an ID and going through turnstiles is clearly associated with the culture of rules. The news of issuing IDs to all employees caused an uproar. However, the announcement was followed by an explanation that the check-point system is being introduced to optimally use office space and keep everyone informed on who is currently in the building (all records of people entering the office went directly from the security check-point to an internal portal accessible to employees). The system in fact was re-positioned on the scale of cultures, and its implementation went without a hitch.

Epilogue

Our journey has come to an end. I hope I was able to show how far and wide a corporate culture penetrates all vital aspects of company's life. In this article I introduced you to spiral dynamics, which is not the only existing approach to tackling the issue, but likely one of the most powerful tools to help you understand a company's culture, diagnose problems and accomplish positive change.

[1] Evgeny Shvarts, "from the play The Emperor's New Clothes.

[1] Grace Hopper - PhD, computer scientist, US Navy rear admiral, and ... a woman! "Amazing Grace" has a US Navy destroyer and a supercomputer named after her.

[1] D.Beck, C.Cowan. Spiralnaya dinamika: upravlyaya tsennostyami, liderstvom i izmeneniyami. Moscow, Best Business Books, 2010.

Обзорная статья 13.02.2024